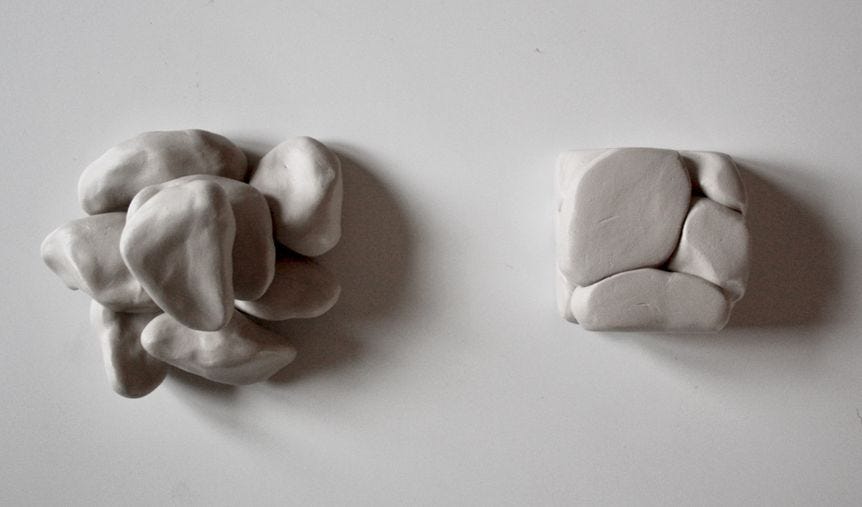

(Image credit Carolina Härdh, sculptures inspired by Jonna Bornemark’s work)

Every patient is unique, with some common basic and measurable features and parameters. For a couple of decades now, healthcare has professed to be patient centered. But the prevailing culture of “quality” (and the reality of getting paid for what you do) has us spending at least half our time documenting for outsiders, who are non-clinicians, the substance and value of our patient interactions. That means our patients get (at best, depending on how clunky our EMRs are) half of our attention and others get half.

But of course, if you really wanted to be patient centered, you’d have to ask what patients actually care about, like their blood pressure or their cholesterol, their anxiety or their sore knees. Their answers may not align with the payers’ priorities. And then what…

Parents raise their children and never have to file any reports on how they do it. I believe clergy can still counsel their parishioners without filing reports. But doctors, nurses, nurses aides and physical therapists are trapped in the tyrannical dichotomy of “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen”, which actually forces us to do less for our patients just so we will have time to document what we did do. We are, to varying degree, robotniks in a big, inhumane corporate and federal healthcare billing machine these days. (My school teacher lady friend tells me teachers are in a similar situation to mine…)

Perhaps the most striking example of the micromanaging and patient-uncentered mandates we are subjected to is the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit: Miss one thing, like offering HIV screening to 80 year old straight-laced French speaking, monogamous and devout Catholics in Van Buren, Maine and risk getting your payment retracted. But we are not mandated to ask about personal life goals or how to balance seniors’ independence with reliance on their children.

Which is more real? The work we do, face to face or even screen to screen, behind closed doors with our patients, or the EMR documentation we produce as a result of those encounters? I know many providers generate voluminous notes that don’t reflect in any way what happened in the visit. That is where the money is.

Right now I am reading a Swedish book by philosopher Jonna Bornemark, titled (my translation) RENAISSANCE OF THE UNMEASURABLE – battling the pedants’ world domination. Much of it is about how the professions of caring for others have been reduced to protocols and reporting systems that make it harder to do what we were trained and developed a passion for. It talks about how checklists and workflows devalue and discourage the powerful creativity that arises when professionals interact with their unique clients and with each other. She anchors all this in the writings of philosophers Cusanus, Bruno and Descartes. It talks about the unknowable, which is something pedants usually don’t want to think about.

Basically, according to Cusanus, there are two models of knowledge, Ratio and Intellectus. Ratio is the possession of measurable and definable information, which basically fits with generalizations we humans make. Beyond that is what is not known. Our modern way of thinking is perhaps that this is simply what we don’t know yet, but eventually can learn or understand. Intellectus is a form of curiosity that scans the horizon of the known or knowable. It asks “what is” and can thereby sometimes make classification and counting possible, but far from always.

People who have Ratio but completely lack Intellectus, Bornemark describes as pedants.

Pedant is a common word in the Swedish language, but not so common here. It means someone with superficial knowledge, focused on perfection of form rather than substance. Words like stickler, nitpicking and OCDreverberate with the notion of the pedant. The Intellectus archetype is what professionals have always strived to emulate.

(Bornemark has a few books available in English that I know of. She is the editor of one with a title that really intrigued me, EQUINE CULTURES IN TRANSITION – Ethical Questions.)

Henrik Sjövall, professor emeritus at Gothenburg’s department of molecular and clinical medicine (that sounds like the title of a man who knows both Ratio and Intellectus) writes:

Bornemark’s discussion of Cusanus’s concept of Intellectus centers on the distinction between the unknown and that which is not yet known. She notes that Ratio accepts only the latter, because according to Ratio, everything can be measured and weighed provided you have sufficiently good methods, which in principle can replace the “flummery” of Intellectus. Intellectus responds with the circle metaphor: a polygon will never be the same as a circle. Oh yes, it can be, provided there are enough of sectors, Ratio responds… Then tell me what a patient’s narrative weighs, says Intellectus. It simply consists of the answer to a lot of yes and no questions, Ratio retorts, and it is dead easy to measure.

He continues:

Bornemark writes that Ratio has, in principle, already won that battle and Intellectus is in retreat, as most people consider him difficult. A manifestation of this is all these algorithms and patient care plans with checklists that inundate us. Triaging in the emergency room is part of the same way of thinking, a rough sorting based on the outcome of a number of objectively measured vital parameters. The next step in that chain is, of course, the introduction of artificial intelligence as interrogator and information sorter, and maybe eventually as a decision-maker without the patient having to meet a doctor at all…

It would be cheap and good, right?

What are the counterforces to this development? I am active in the Swedish Association for Narrative Medicine (anyone interested is welcome to join), an association that wants to focus on something that cannot be measured and weighed, namely the patient’s story. We are making an effort to stop or ideally reverse this development. In other words, to train Intellectus doctors.

I read in the Wall Street Journal about a forthcoming book about living with autism – not being able to fully understand the nuances of facial expressions and intonation, for example. It seems to me that those things are exactly what good clinicians excel in. Such things make them Intellectus practitioners and elevate their work to a level beyond Ratio, the territory some hope will ultimately be the domain of Artificial Intelligence. I, for one, don’t think AI will ever move beyond Intelligence to Intellectus.