Before EMRs, information flowed through nurses and secretaries (remember that word, anyone?) to us doctors. And it was generally prioritized, if not with clinical expertise, at least with a healthy amount of common sense. This allowed us to get to urgent and important results and messages before less urgent ones.

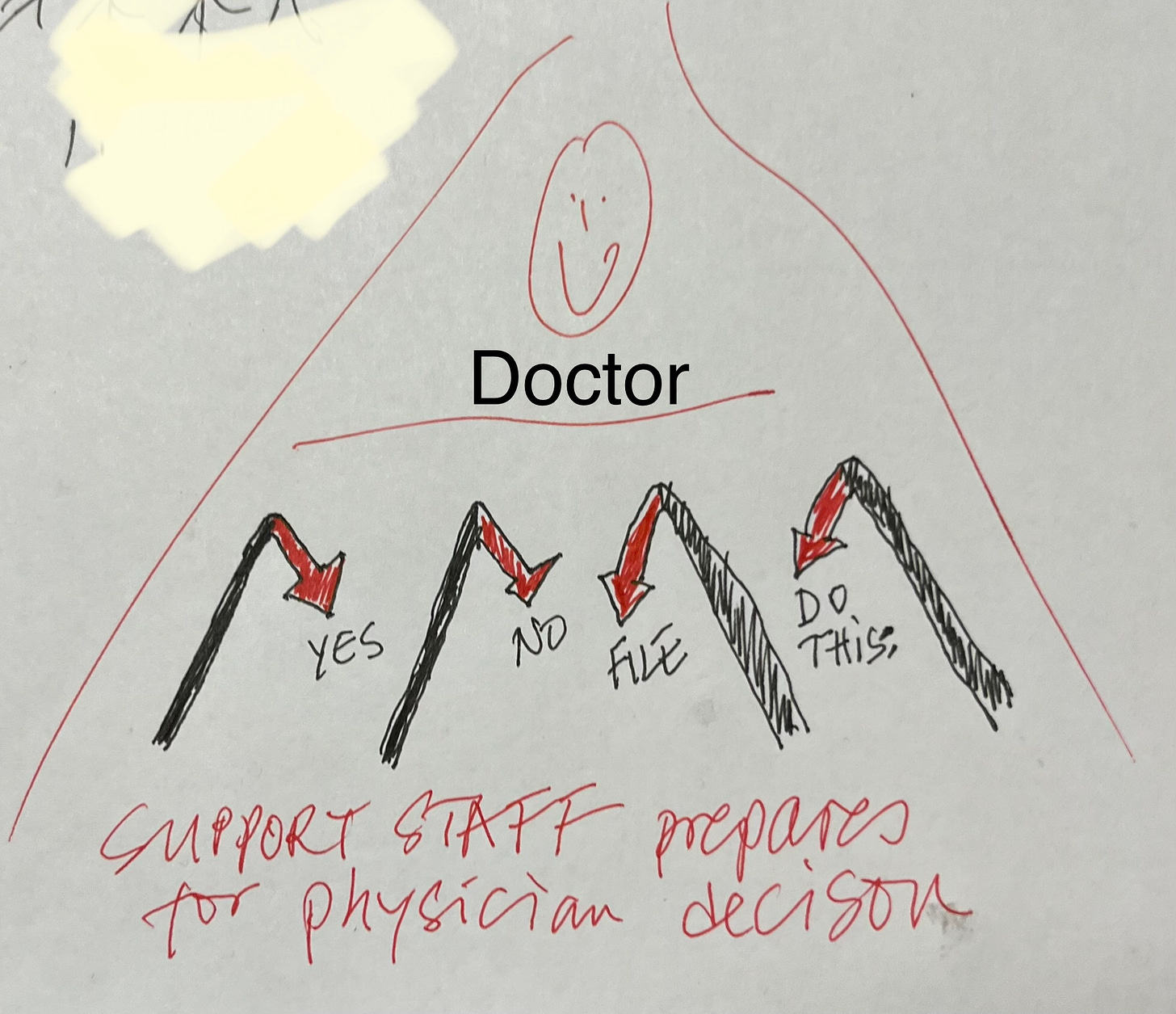

Even with early EMRs, paper reports would arrive, get sorted, reviewed and acted on before getting scanned in - often with a quick signature and comment scribbled on the bottom. We might note “repeat 1 year” on a normal mammogram or instruct our staff to “Order CT w contrast” on an abnormal chest X-ray. This was a very quick way to review and delegate. The doctor did what only the doctor could do and other staff did the rest. It was even possible to have a standing order that all women with a normal mammogram get scheduled for their next one automatically.

You can visualize the flow of information as a triangle, flowing from many sources at the base through support staff to the clinician, at the top, as the decision maker. The information would then flow back one step down the triangle to the person who presented it to the doctor.

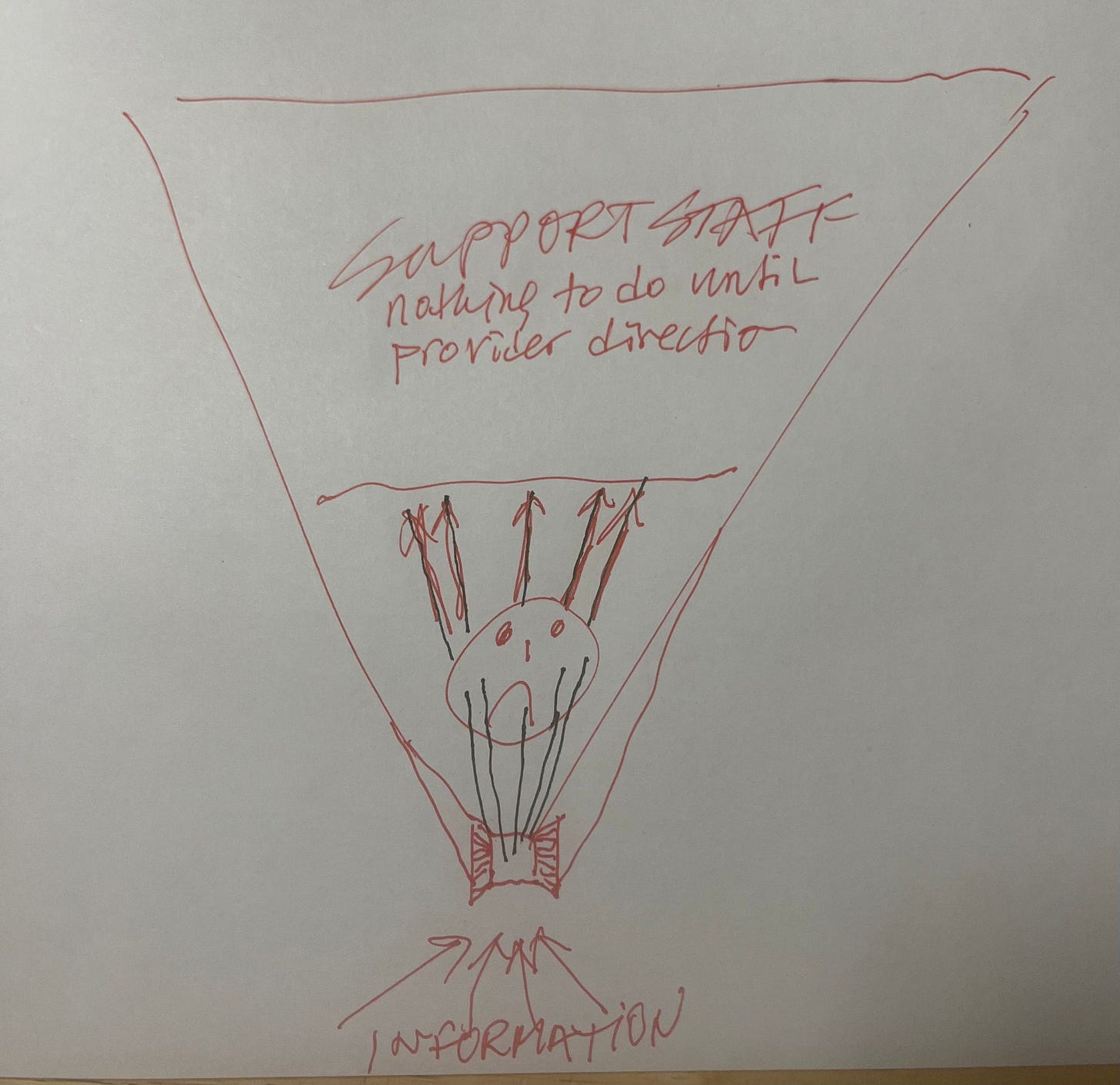

(Paper napkin sketches © A Country Doctor Writes, LLC; may be reproduced with back link.)

We often communicated verbally and in person. The nurse or medical assistant might tell the doctor on a Monday morning, “these three patients were in the ER this weekend and need follow ups this week, Mr Jones ideally no later than Tuesday”.

Working this way, we were a team. We communicated effectively in real time.

Now, even if we work at desks in the same room, our communication is mostly asynchronous, very much like email. And our inboxes offer few ways of prioritizing information.

And the worst and most dangerous difference between the old and the new information flow through the EMR is that all results and outside reports arrive directly in the doctor’s electronic inbox (and we often have dozens of different inboxes to monitor) UNSEEN BY ANYONE ELSE.

So it is now, theoretically, up to the doctor on a Monday morning to open up and read the weekend ER reports (scrolling through multiple pages in a small view box on the computer screen, looking for the followup instructions) and then electronically forward the report with comments to the support staffer.

The reason we have to do this is to generate an electronic record of when we read the report and what we did with it. This seems to largely be for liability purposes, so that if anything goes wrong, the doctor can be held responsible.

Today’s information flow triangle is upside down: Its foundation, read entry point, is the medical provider. It is the team leader who has to touch and timestamp (in the background) everything and then electronically spoon feed it to the other team members.

This “workflow” makes sense to computer people, statisticians and malpractice attorneys. But it makes doctors spend inordinately more time staring at their computer screens and less time with their patients.

I guess if EMRs were more nimble than they are now, this upside-down workflow would be slightly less cumbersome, although equally dangerous.

It is disheartening to hear about AI and how smart computers are supposed to be these days while we have to follow awkward, multistep computer routines to accomplish things that Alexa can do effortlessly in peoples’ homes.

But the bottom line is that, in today’s mostly fee-for-service environment, doctors are under pressure to generate revenue, which means face-to-face encounters. Time at the computer, reading inboxes, refilling prescriptions and responding to patient portal messages are things that practices generally don’t get paid for, so doctors seldom have enough (or any) time set aside to do them.

With all the worry we constantly hear about physician shortages and the burnout epidemic among us, medical practices really must question the current way they want us to manage the flow of information in our offices. It is hugely inefficient and actually quite dangerous.

In what other type of business does the decision maker open the mail and then hand it to the support staff?

How would it be if we borrowed a page from the paper chart playbook and figured out better ways to leverage physician input than we have with today’s EMR-imposed bottlenecking of information? I think it’s high time we turn the triangle back right-side-up!